Fed-Treasury Coordination in Plain Sight

The Treasury's recent Quarterly Refunding Announcement laid out explicit Fed-Treasury coordination with the effect on markets being identical to QE.

What is a Fed-Treasury Accord…

When people talk about a “Fed-Treasury Accord,” they are usually referring to the landmark 1951 agreement that established the modern independence of the U.S. central bank. It ended a period where the Federal Reserve was effectively “captured” by the Treasury Department, as during that time the Fed had an obligation to peg interest rates on government bonds to artificially low levels to ensure the government could finance the costs of WW2 without interest payments skyrocketing. The cost of this policy was inflation. This "divorce" restored the Federal Reserve's independence to conduct monetary policy focused on price stability rather than financing government debt.

After the war, inflation began to rise and the Fed wanted to raise interest rates to cool the economy, but the Treasury and President Truman insisted on keeping rates low to keep the cost of national debt down. This created a massive “tug-of-war” over who controlled the nation’s money before an eventual formal agreement was reached on March 4, 1951. The key outcomes were:

Ended interest rate peg: The Fed was no longer obligated to peg interest rates to support the Treasury’s borrowing.

Established Fed independence: The Fed gained the freedom to use monetary policy to pursue economic stability and control inflation, establishing its “dual mandate” framework we see today - maximum employment and stable prices.

Rising concerns of fiscal dominance today are a result of unsustainable government spending levels that are accommodated and enabled by the Fed via continued backstopping of the US Treasury market. Actions of this nature have occurred in every year following the COVID pandemic.

While the 1951 Accord established “independence,” the two institutions very much continue to work together. This can be seen at a smaller scale by the routine Treasury Secretary and Fed Chairman weekly breakfast meetings and on a larger scale via the various crisis response programs. Every year new acronyms are made to obfuscate this lack of independence, whether that’s QE, MSLP, BTFP, RMP, you name it.

Reading between the lines today…

In the Treasury’s recent Quarterly Refunding documents, we have received another glimpse into what this coordination looks like.

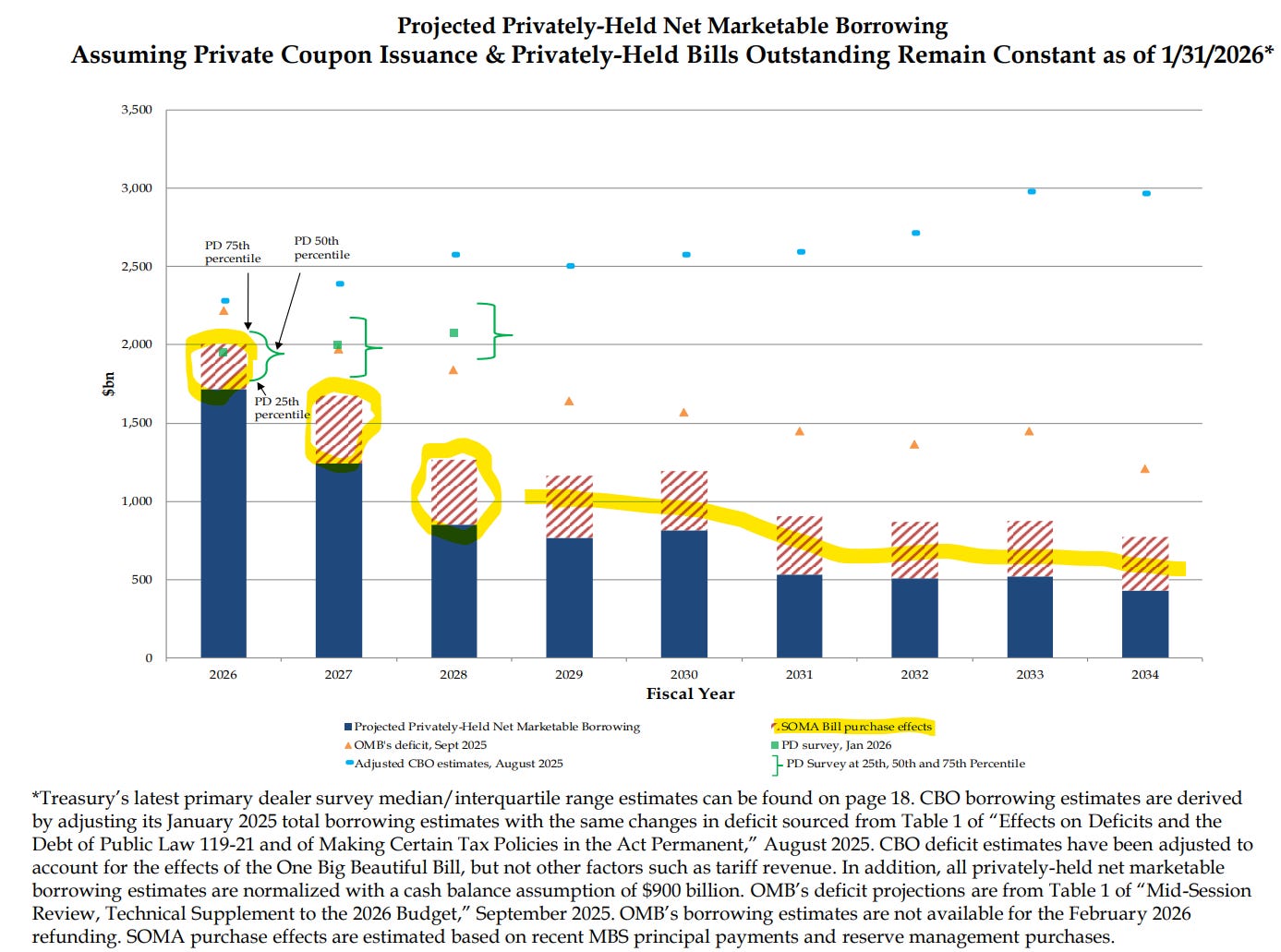

One example is how the Treasury’s projections for debt issuance assumes Fed balance sheet expansion via Reserve Management Purchases (RMP) of bill issuance in the SOMA portfolio, in perpetuity. They show this to account for an increasing portion of total US debt issuance over time, which happens to be new information because Powell and the Fed’s communication on the topic indicated the large $40B/month amount was “temporary few month front-loading” but “thereafter we expect the size of reserve management purchases to decline”. So either this communication was known to be untrue from the start, the Treasury is the one actually calling the shots or they’re taking the liberty to assume the aggressive pace of these purchases by the Fed, but either way, there is inconsistency here.

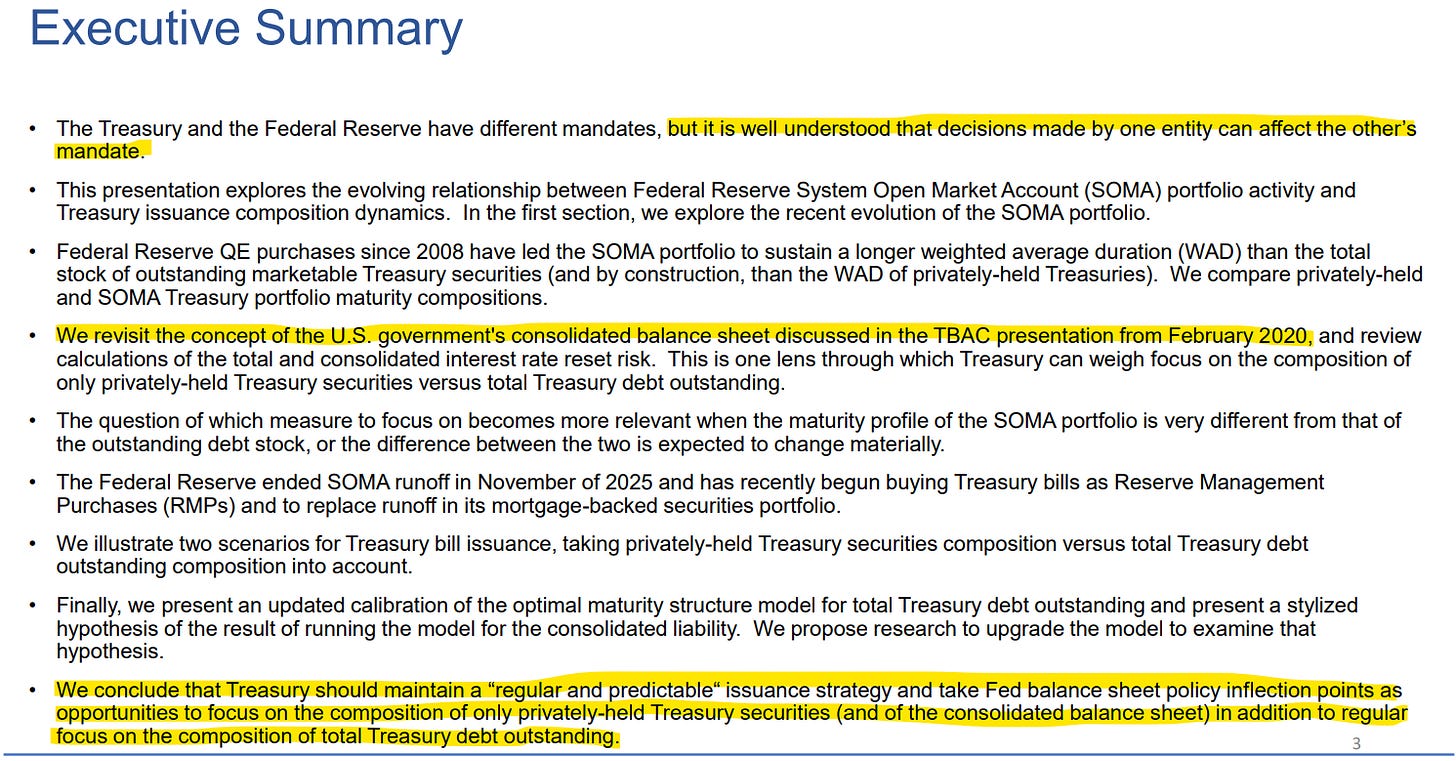

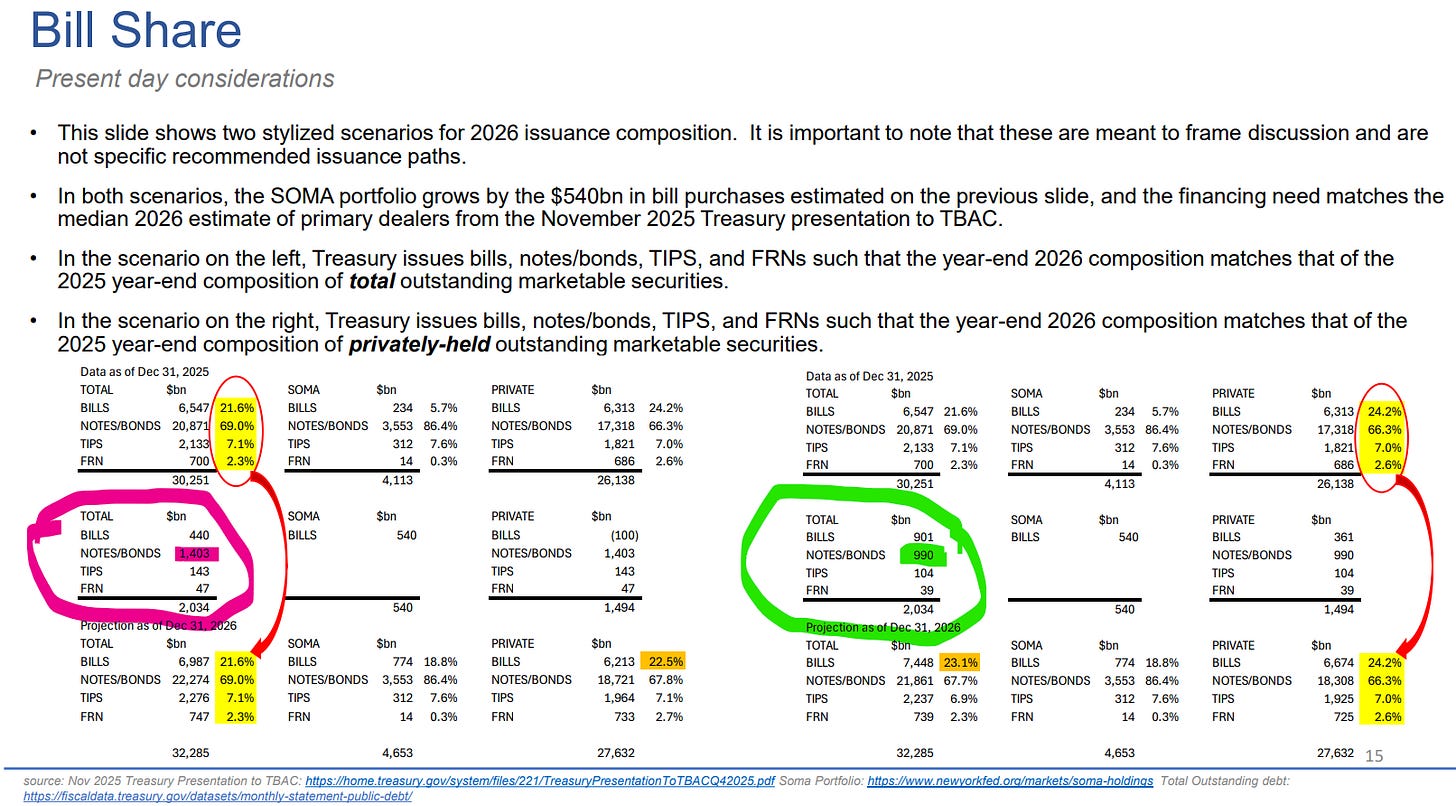

Next we have a section that discusses the “U.S. government’s consolidated balance sheet”, detailing the composition of privately-held and Fed balance sheet Treasuries and the effect of issuance adjustments.

This introduction of adjusting issuance based on the composition of only privately-held Treasury securities can be translated to mean - reducing coupon issuance. This is the clearest continuation yet of the ‘Active Treasury Issuance’ policies introduced by Yellen under the Biden administration, otherwise known as ‘Yellenomics’.

You can see here how the Fed’s unbalanced monetary policy has increased the duration of its balance sheet in tandem with the Treasury’s reduction in the duration of its issuance.

This chart highlights the problem even more clearly. The Fed’s SOMA portfolio owns a much larger share of 10-30 year Treasuries than the privately-held ownership. Said another way, the Fed is suppressing long-term bond yields (likely by 50-100 bps) by having an outsized footprint in this part of the market. This suppression of long-term bond yields has led to a more supported stock markets and the front-end Fed Funds rate remaining abnormally high for too long as a result. This uneven transmission of monetary policy is a key reason for why main street and small businesses have been crushed over the past few years as they borrow off the front-end, meanwhile large cap tech, hyperscalers and AI capex spenders borrow off the long-end and have benefitted from abnormally low funding costs. You can thank the Fed for a large part of the inequality we see across the economy today.

While many are concerned about dwindling Fed independence, the trend has been in place for many years now and is just a continuation of previous policies. This latest release from the Treasury is significant because its effects on markets is identical to additional QE - the Fed increases its balance sheet and the Treasury takes duration out of the market to “meet the new Fed policy demand”.

Other interesting tidbits…

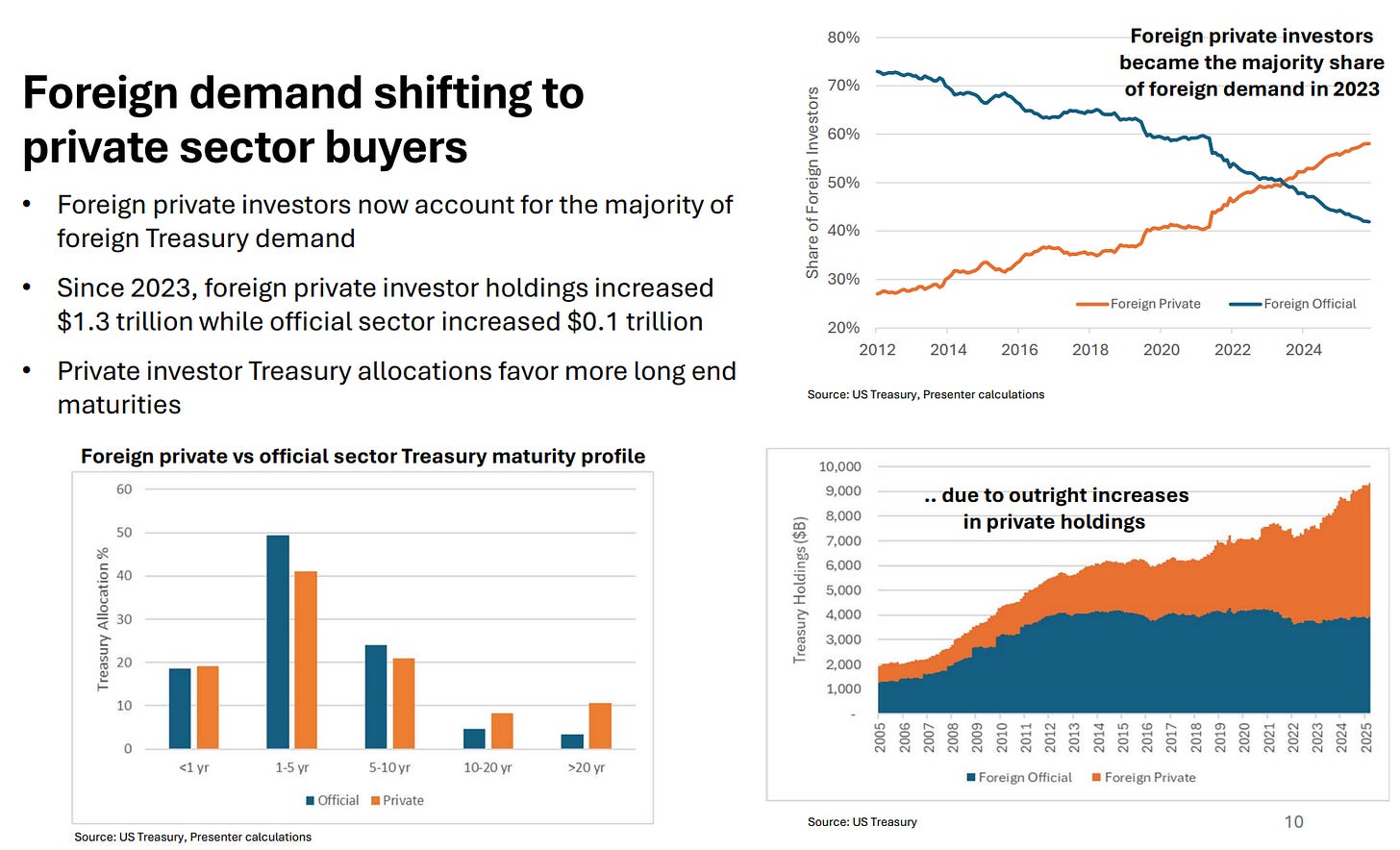

They also highlighted the shift in foreign demand to private sector buyers. This is most notable on the long-end maturities.

While the Treasury highlights private investors’ increased price sensitivity, that doesn’t jive with their increased involvement in the long-end despite “some domestic sovereign alternatives offer higher yields than US Treasuries on a currency hedged basis”. Most believe this rise in foreign private sector holdings is the offshore hedge funds engaging in the basis trade which continues to grow.

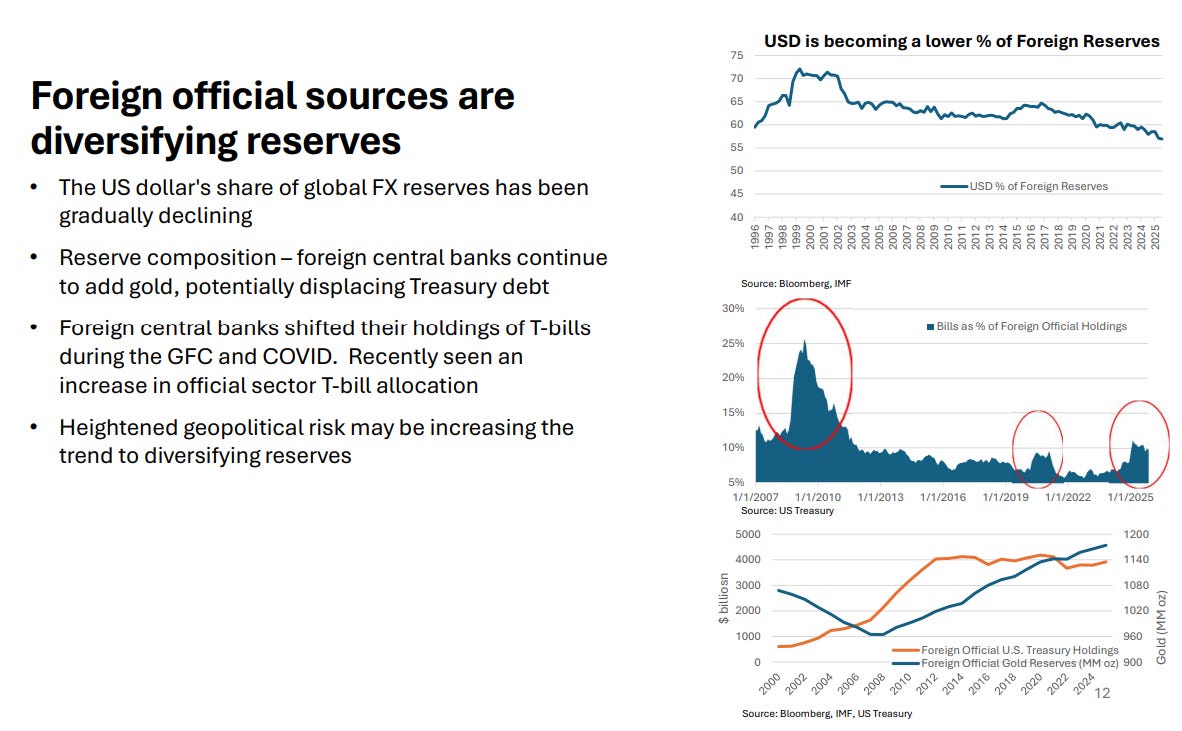

I liked this discussion of the US dollar’s declining share of global FX reserves being offset by rising gold holdings. It’s interesting to me that Powell wouldn’t talk about this but the Treasury is.

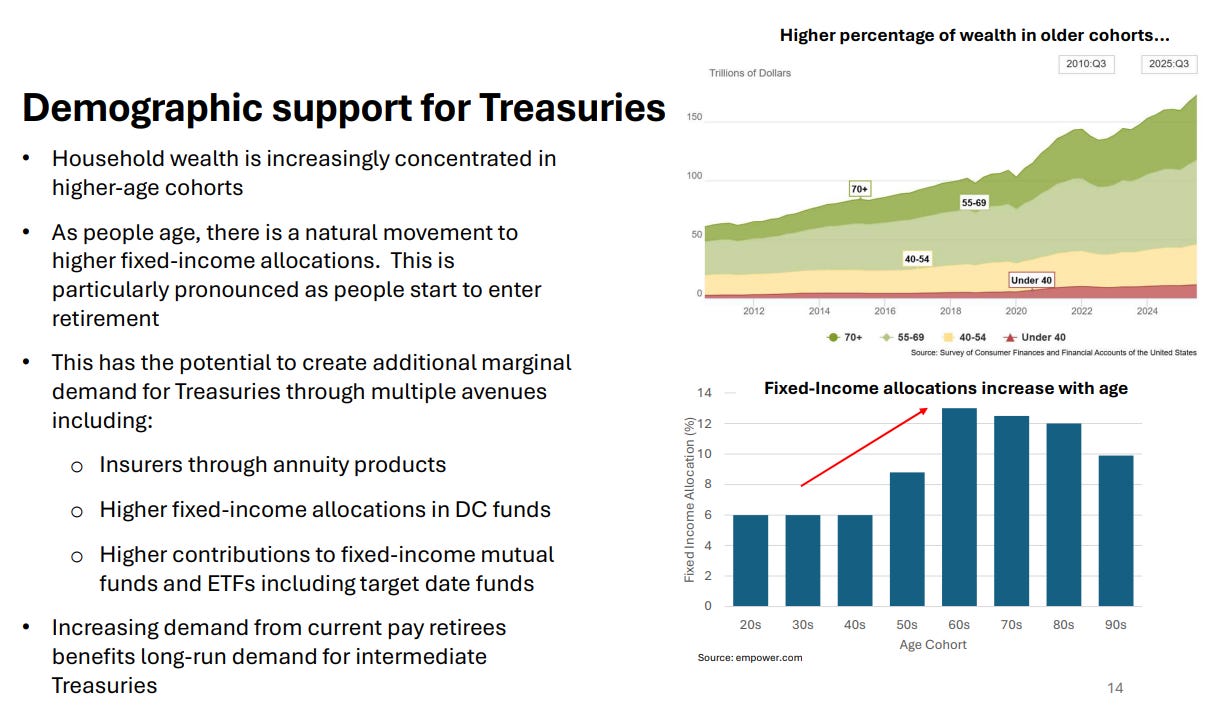

They also highlighted aging demographics in the US as one of the drivers of Treasury market support. This is actually needed as Baby Boomers accept lower and lower real returns as they age and retire and effectively help to subsidize the financial repression for younger generations.

Market implications…

To summarize, the bull case for gold is unlikely to go away anytime soon. We have stock markets at all-time highs and unemployment rate below <4.5%, yet the US government has restarted quantitative easing to support the bond market again without any crisis type event. It’s February of a high stakes midterm election year with even more consolidation of power occurring in the coming months with new Fed leadership. Do you think this type of behavior is going to increase or decrease in the next 12 months?

Thoughtful piece thanks.

I thought the consensus take on Warsh was that he'd definitely deliver the rate cuts (which Trump surely forced him to agree to) but that he was going to try to reduce the Feds balance sheet to reduce the K shaped inequality. How can he support the long end without stimulating markets?